I’m very happy to share that our work that evaluates synthetic data sharing as a privacy mechanism titled “Synthetic Data- Anonymisation Groundhog Day” was accepted for publication at USENIX Security’22. The final version can be found here. Below, I shortly summarise our key findings and conclusions.

A short summary

What motivates our work? Both, practitioners and researchers, often present synthetic data as The Privacy Solution that addresses the shortcomings of traditional anonymization and enables data sharing with a much better privacy-utility tradeoff than row-level sanitisation.

But so far there is no evidence that this claim actually holds true. There is no rigorous analysis that shows that synthetic data indeed provides better privacy protection at a lower cost in utility than traditional sanitisation.

What we did? We designed and implemented an evaluation framework that allows us to quantitatively assess this claim. We evaluated a wide variety of standard and differentially private generative models and assessed whether they indeed provide better privacy-utility tradeoffs for high-dimensional data sharing than traditional sanitisation.

What we found? In essence, we find that synthetic data is far from the magic silver bullet it is promised to be. The tradeoff between preserving fine-grained statistical patterns and protecting the privacy of outlier records in high-dimensional data releases remains.

Synthetic data sampled from models without explicit privacy protection leaves outliers vulnerable to linkage attacks. Differentially private model training increases the privacy gain of synthetic data sharing but does not retain sufficient data utility for many use cases.

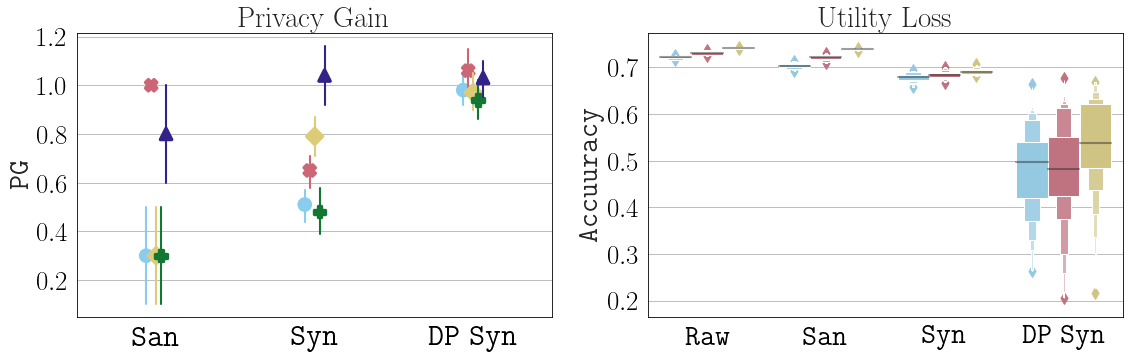

For instance, in the graph below on the left side we compare the privacy gain of (differentially private) synthetic data publishing to that of traditional sanitisation. We can see that while sanitisation, as expected, leaves some outlier records vulnerable to privacy attacks (privacy gain far below 1), synthetic data provides a higher gain for most records and differentially private synthetic data further improves this gain. However, as we show on the right, this comes at a significant cost in utility. If we use the (differentially private) synthetic data instead of the raw or sanitised data to train a machine learning model, the model’s performance drops substantially.

Worse, not only does synthetic data fail to improve over the privacy-utility tradeoff of traditional anonymisation, we also show why it is actually much less suitable as a privacy mechanism: The privacy gain for individuals and the utility loss for specific use cases is not predictable. This property make synthetic data a pretty bad privacy mechanism.

What else did we learn? Our empirical evaluation of two differentially private models frequently used in practice revealed that their existing implementations violated important theoretical assumptions of the differential privacy model. Therefore, both models did not provide the formal guarantees they promised to and left outlier records vulnerable to privacy attacks.

We suggest a way to avoid this leakage but observe that if a model’s implementation meets all assumptions and provides strict privacy guarantees, its utility decreases substantially. This is not unexpected given all the previous literature that shows that privacy for sparse, high-dimensional data is hard. A great summary of this fundamental tradeoff can be found in this excellent blog post by Arvind Narayanan and Vitaly Shmatikov.

This and the rest of our findings highlight once more the importance of empirical evaluations for building privacy-preserving systems. To help others with this, we publish our framework as an (hopefully) easy-to-use open-source library and have started multiple collabs to help people use it.

Key takeaways

Synthetic data is far from the holy-grail of privacy-preserving data publishing. The promise that it provides a higher gain in privacy than traditional sanitisation at a lower cost in utility rarely holds true.

On top of that, synthetic data, in comparison to deterministic sanitisation procedures, does not allow us to predict what signals will preserved and what information will be lost. This leads to a highly variable privacy gain and unpredictable utility loss.

Photo by Pixabay from Pexels